If you’ve read my posts up to now, you’ll know how strongly I feel about what makes a book work or not. And if you’ve read my “10+ Rules” page (see the link above) and I tell you that the first chapter of this book is called “The Jokers Club” (sic) you can pretty much guess what I feel about this book.

If you’ve read my posts up to now, you’ll know how strongly I feel about what makes a book work or not. And if you’ve read my “10+ Rules” page (see the link above) and I tell you that the first chapter of this book is called “The Jokers Club” (sic) you can pretty much guess what I feel about this book.

I found this book because I was looking for kids’ books about dyslexia and this was the only book that came up in the catalogue besides the “Hank Zipzer” books. (Of course, this may not reflect the actual situation on the shelves in the Portage District Library, because their extraordinarily quirky catalog will often return items having nothing to do with your search and leave out items you know they have that actually are related to your search.)

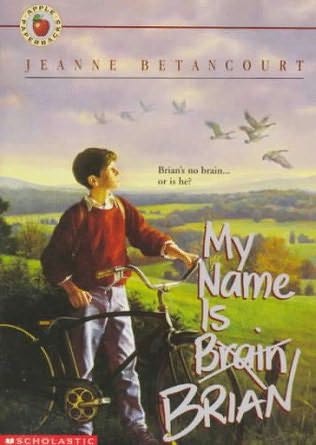

I didn’t recognize either the title or the author (who turns out to be dyslexic herself), so I grabbed this book which begins by telling how Brian and his three best friends have always been lousy students at school. When he enters the sixth grade, however, he has a new teacher who realizes that Brian’s previous troubles are not due to laziness or stupidity, but to his previously unrecognized dyslexia. It takes a lot of hard work and extra tutoring to get over his difficulties, but Brian more than makes the effort. By the end of the book, he reflects on his dyslexia:

I know it’s never going to go away. But it’s not going to get worse, either. And I’m going to get better and better at the thinking things I am good at, like understanding birds, how things work, and having creative ideas. (123)

If this paragraph is meant to reassure kids with dyslexia that while things will never become perfect, they will get better, I suppose that it does, albeit in a heavy-handed sort of way. And this is mainly due to, yep, you guess it—voice. I can understand getting better at understanding birds, but I think a real kid (or even a real adult) would say “knowing about birds.” What I don’t understand is how you can get better at “having creative ideas.” Maybe this is a just a dyslexia thing. How in the world would I know?

This is why we need authentic insider voices to write about the struggles of young people with dyslexia, rather than resorting to clichés to bulk out our writing, so that those of us on the outside have a better idea of what it feels like to be on the inside. Does Betancourt do a better job of depicting the dyslexic experience than Henry Winkler? She’s certainly less annoying, and for that reason alone, I’ll take this book over a pile of Hank Zipzer books. But are either of them accurate in their depictions? I just don’t know. I don’t know anyone with dyslexia who has read these books and can give me their insider’s point of view on them.

But back to that “Jokers Club” thing (if you are wondering what sic means, it means that I have transcribed this exactly as written, because there should be an apostrophe after the “s” like this: Jokers’ Club). This club of four goof off and do poorly in school—Brian because of his dyslexia, the other members for different reasons that will be discovered later, and which will ultimately tear this club apart.

I suppose, based on my professional knowledge of dyslexia, that Betancourt succeeds in depicting what it’s like to suffer from dyslexia. Where she really shines is in her description of how friendships change, sometimes becoming stronger, sometimes breaking apart, right around the first stirrings of adolescence. This generally occurs right around middle school, which is, after all, a time when people who are friends tend to become people who used to be friends. Because this often occurs without our being aware of its happening, or being aware of the reason for its happening, it can be a disturbing and confusing experience. Betancourt plays fairly, if clumsily, with this aspect of the book and its implications.

The main reason this book got published in the first place is that it came at a time when dyslexia was a hot-button topic—celebrities were practically tripping over each other to come forth and own up to being dyslexic, although few of them have stuck with it now that ADD, autism, color-blindness and who knows what else is the current fashion disability in Hollywood. Any book with dyslexia as its central talking point was looked upon favorably. But we’ve moved on since then and hopefully become a bit more sophisticated.

I really would be happier if this were a story about four close friends who end going their separate ways by the end of sixth grade. The Jokers’ Club ceases to exist because each member has his own prerogatives which he now places ahead of the interests of the club. This kid drops out because he wants to be badder than the rest, this one because he wants to be better, this one because he’s smarter, and this one because he just happens to have dyslexia.

I think I’ll let it rest here. As a book about a kid with dyslexia, if does an adequate, if somewhat heavy-handed, job. (Besides the “club” thing, there is also the “brain” thing, alluded to here in the title and an annoying constant in the Hank Zipzer books. Do dyslexic people really think that much about their brains and how they work?) As a book about the dissolution of friendships in the crucible of middle school, it does a fairly adequate job. Not spectacular, but adequate.

Sometimes that’s the best you can hope for.

Ages: Intermediate. Recommendation: A bit didactic, but okay if you can spare the time.

Works Cited

Betancourt, Jeanne. My Name is Brain Brian. New York: Scholastic, 1993.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2010/08/14/my-name-is-brain-brian-jeanne-betancourt/