Hank Zipzer isn’t your average fourth-grader. He’s intelligent, creative, and incredibly likeable. Yet he does terribly at school because he’s dyslexic. Although the “d-word” doesn’t appear anywhere in this book, Hank mentions his brain and his “learning differences” enough for it to become annoying.

I’m starting to feel as if I should get a rubber stamp with the following message: “I really wanted to like this book, but couldn’t, because______________.” I don’t feel bad about this because writing for kids is some of the hardest and most honorable writing there is. I’m not surprised that so many try, nor am I surprised that so many fail. In kid lit, It’s either nothing but net or nothing but air. There isn’t much that bounces off the rim. Such is life.

And yet, there are those books that you really, really hope for. The ones that do hit the rim and bounce off.

A bit of background is in order. Henry Winkler is an American actor best known for playing Arthur “The Fonz” Fonzarelli in an early 1970’s US sitcom called Happy Days. If you’re too young to remember that, he also played the dad in the film version of Holes. Happy Days was kind of a big deal back in the day — so much so that the leather jacket Henry Winkler wore in now displayed in the Smithsonian Institution.

For a while there in the United States, celebrities were practically tripping over each other in order to admit to some disability or other. Most of them admitted to being dyslexic, or allergic to shellfish, or something like that. (Which pretty much tells you how I feel about celebrities and their problems, but that’s really the subject of a whole other post.) But Henry Winkler was one of the first, and therefore, I didn’t have any trouble believing him. Besides, he was the Fonz! The Fonz doesn’t lie, because the Fonz doesn’t have to lie.

So yes, I really wanted to like this book. And I did like it, after a fashion, which means that if you’re nine or ten, you’ll probably be able to read this, enjoy it, and have no problems with it. And if you’re young and dyslexic, then you’ll probably love this book. Outside of those parameters, however…

Henry Winkler is to be commended for not even trying to claim to have written this book on his own. He works with Lin Oliver, who, according to the “About the Authors” (note the plural) blurb at the end of the book, “is a writer and producer of movies, books, and television series for children and families.” That’s a pretty impressive credential. A lot of celebrities “write” books, but they are really ghost-written by someone else. And even when a co-author is listed, I wonder how much the celebrity really wrote.

Henry Winkler actually had a lot of involvement with the writing of this book. And that’s the problem with this book. It reads less like a fictional story and more like a thinly disguised autobiography of Henry Winkler, which is what it is, of course. Notice the similarity between “Henry Winkler” and “Hank Zipzer”? Henry Winkler is probably too close to his material here. In fact, the entire book reads a bit like a season of Happy Days, just one crazy improbable situation after another.

Of course, Hank eventually gets help from the new music teacher, Mr. Rock. Just reading that makes my head start to throb, because now we have The Character With The Obviously Symbolic Name. You know, I could write a dissertation on character names in children’s literature: which ones work, which ones don’t, and why. I don’t have a problem with symbolism, except when it’s forced, like this example. If it’s there in your rough draft, as a writer you should play around with it and make the most of it in later drafts, the way a gemcutter polishes a jewel, but if it’s not there to begin with, just leave it alone, or you end up relying on cliché and stereotype.

Of course, the saddest thing of all is that Henry Winkler and Lin Oliver just can’t get the voice right. Throughout this entire book, I never had the feeling that I was listening to a ten-year-old telling a story, I had the feeling that I was listening to an adult trying to sound like a ten-year-old telling a story. When the voice is right in a kids’ book, it’s golden; when it’s wrong, like in this example, it’s just sad and wonky, and a little bit creepy, to tell the truth.

I had a chance to ask Gary D. Schmidt about this, which made me happy because he’s one author who can get the voice right. (Jack Gantos is another, along with Mark Haddon and John van de Ruit.) He said that a good, strong voice comes from listening to your character telling the story to you. You actually have to hear the character’s voice in your head. And to tune it to that voice, you have to be prepared to do a lot of revision.

There’s a lot in that. I could basically divide the entire world of kid/tween/teen lit into two groups: those with a good, believable voice, and those without. This book falls into the latter, because the author was desperate to tell a story. But to get the voice right, you can’t tell the story yourself, you have to let the character tell the story through you. You have to get out of the way of your character so that your character is front and center, not you.

That’s no small feat, and it’s no wonder that so many writers can’t achieve it. What I wish here is that instead of writing a nominally fictional book that has a lot of autobiographical elements to it, that Henry Winkler had just sat down and written his own autobiography for kids. Then he could have gotten the autobiographical stuff out of his system and just concentrated on story when it comes to Hank Zipzer.

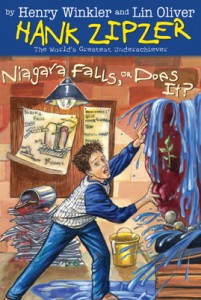

Winkler, Henry, and Lin Oliver. Hank Zipzer: Niagara Falls, or Does It? New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 2003.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2010/05/29/hank-zipzer-niagara-falls-or-does-it-henry-winkler-lin-oliver/