One of the worst things about being an adult is that when you read a really good kids’ book, you’re still focusing on all those “English teacher” things: theme, symbolism, characterization, etc. It is all too easy to forget that when a young person reads a book, they’re not looking at the trees, but rather at the forest. They want to be entertained, and if a book doesn’t entertain, then they’re going to be disappointed.

Even as an English teacher, however, I’m still looking to be entertained. And this book doesn’t disappoint.

I was originally attracted to this book by its cover (the US version of which is to the left), which gave off a vague Robinson Crusoe feel. (A great book, by the way.) Of course, the dog, apparently a border collie, doesn’t hurt, either.

Michael is an English boy whose parents lose their jobs in a local brick factory, and then decide to buy a sailboat (the Peggy Sue) and sail around the world. The idea of taking two adults, a boy, and their dog, Stella Artois (along with a football–make that a “soccer ball” for US readers) around the world as a response to a lack of employment is, frankly, a crazy one, which the story’s narrator, Michael, makes explicit:

Of course it was a madness. They knew it, even I knew it, but it simply didn’t matter. Thinking back, it must have been a kind of inspiration driven by desperation. (13)

Even though this book was published some ten years ago, this idea rings true now, given the worldwide economic meltdown. Crazy times invite crazy responses. This family is no different, and I am in some ways surprised that my admittedly hasty appraisal of the cable news networks fail to highlight any such exploits by the recently desperate.

Anyway, Michael and his family set off, with their dog and with a football signed by Michael’s friend Eddie (as if Eddie were a big-time footballer; such is the power of kids’ imaginations). They make their way around most of the world, with Michael’s mum serving as captain, before Michael, Stella, and the football are washed overboard during a night-time storm.

Michael is saved, in an effective dream-like way, which in his exhausted desperation he visualizes as being brought back on board the Peggy Sue.

The strange thing was that I didn’t really mind [drowning]. I didn’t care, not anymore. I floated away into sleep, into my dreams. And in my dream I saw a boat gliding toward me, silent over the sea. The Peggy Sue! Dear, dear Peggy Sue. They had come back for me. I knew they would. Strong arms grabbed me. I was hauled upward and out of the water. I lay there on the deck, gasping for air like a beached fish. (45)

Of course, this isn’t a dream, and when Michael awakes, he finds himself on a deserted island. The island’s only other inhabitant is Kensuki, a Japanese doctor who was the sole survivor of his ship’s destruction during WWII.

Morpurgo effectively creates tension and fear, without allowing it to become too overpowering. When Michael awakes the day after his rescue, he begins exploring:

When the beach petered out, we had to strike off into the forest itself. Here, too, I found a narrow track to follow. The forest became impenetrable at this point, dark and menacing. There was no howling anymore, but something infinitely more sinister: the shiver of leaves, the cracking of twigs, sudden surreptitious rustlings, and they were near me, all around me. I knew, I was quite sure now, that eyes were watching us. We were being followed. (53)

That’s some forest, I want to tell you! (I’ll have more to say about that forest later, if you don’t mind a few spoilers. And for those of you who teach writing to your charges, modeling what actual authors do, take a look at that very sophisticated use of a colon.)

I don’t want to give too much away here, but needless to say that although Michael and Kensuke get off to a poor start (even though Stella knows better!), the two of them eventually form a strong bond and help each other out. Does this book have a happy ending? It does, although it is probably not the happy ending that most readers are expecting. Thus, it gives readers much more than they bring to it. I happily shove this book into your hands.

To see what the author has to say about the creation of this book, check out his website.

Chapter book. Age level: Middle school and up. Recommendation: A great read.

That said, however, I do want to put on my “English teacher gloves” and take a slightly closer look at some of the things I really liked about this book.

Warning: The rest of this post contains spoilers!

For anyone who has ever spent some time on the open water, even if that open water is the nearest lake, you don’t have to exhaust much energy to imagine just how vast the world’s waters are. “They say that water covers two-thirds of the earth’s surface,” Michael tells us, perhaps summarizing an encyclopedia entry. “It certainly looks like that when you’re out there, and it feels like it, too” (18). Now, multiply your own local experience by a thousand, or a million, and you have some idea of what it’s like to be on the open ocean. To be washed overboard in a strange ocean, in a place you have never heard of, and, given the one-in-a-million chance of finding land, you are sure to wash up on a shore where none of the inhabitants speak your language, is to be very desperate, indeed.

Yet Michael never stops believing in his imminent rescue. One of the most powerful themes that resonate through this book is the power of belief. As Michael says:

I would close my eyes tight shut and pray for as long as I could, and then open them again. Every time I did it, I really felt, really believed, there was a chance my prayers would be answered, that this time I would open my eyes and see the Peggy Sue sailing back to rescue me, but always the great wide ocean was empty, the line of the horizon quite uninterrupted. (78)

For Kensuke, belief is equally powerful. When Michael tells him that there is a chance that his family could have survived the bombing of Nagasaki, Kensuki responds:

No….They are dead. That bomb was very big bomb, very terrible bomb. Americans say Nagasaki is destroyed, every house. I hear them. My family dead for sure. I stay here. I safe here. I stay on my island. (137)

If I may make a philosophical detour here (and you’ve read so far, so I assume you won’t mind if I do), keep in mind that distinction that Nietzche made between the Apollonian and Dionysian in literature. For Michael, despite what we may think about the open ocean, that ocean represents a very Apollonian, very ordered and structured environment. “I was always kept busy,” he tells us. “I’d be lying if I said I loved it at all. I didn’t. But there was never a dull moment” (19). For Kensuke, his island represents much the same thing. As Michael discovers after being rescued from a jellyfish attack, Kensuke has created a sense of order out of the chaos of this island. Listen as Michael describes Kensuke’s cave:

Apart from the roof of vaulted rock above, you would scarcely have known it was a cave. There was nothing rudimentary about it at all. It looked more like an open-plan house than a cave — kitchen, sitting room, studio, bedroom, all in one place. (98)

Essentially, while Michael views the outside world as essentially Apollonian — a place of light, clarity, and order — Kensuke views it as a place of disorder, conflict, and personal loss. Michael longs to return to the outer world, while Kensuke shuns it. Despite these differences, and despite Michael’s numerous attempts to contact that outer world, the two of them still manage to form a strong bond, one which eventually transcends the novel’s pages.

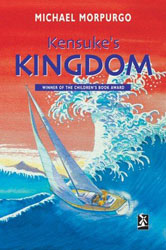

There are just two more things I want to mention. The first deals with the book’s covers. Above, you can see the cover of the book as it was published in the United States. This is the UK version of the book’s cover:

The difference is clear. In the American version, Michael (and Stella) are front and center, perhaps reflecting the American ideal of the individual over society and over nature. Michael may be on an island, or he may be on vacation in Florida. It isn’t clear, but it doesn’t matter either way. Despite the title, the cover makes clear that this is Michael’s story, that whatever Kensuke offers, apart from the title, is not nearly as important as Michael’s own experience. This is a book about Michael, about the individual.

In the UK version, on the other hand, Michael and Stella are reduced to mere blobs of acrylic paint. The emphasis here is not so much on the individuals (boy and dog) involved, as their struggle over nature. (And oddly, although the storm which washes Michael overboard occurs at night, the scene depicted occurs in the day. Clearly, the publishers didn’t want anyone to mistake this for a scary book.)

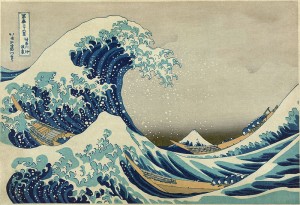

In fact, the UK cover bears a very slight resemblance to Hokusai’s eighteenth-century painting “The Great Wave off Kanagawa”:

At the very least, the UK version pays some homage to the Japanese culture which plays so important a role in this book. And it also emphasizes the tremendous role that nature plays in this book.

There’s just one more thing I want to mention about this book, and in case I am starting to bore you, I should perhaps quit while I am ahead. But indulge me for a moment, won’t you?

As it turns out, Kensuke is wrong: his family survived the bombing of Nagasaki because they were visiting relatives in the countryside. The postscript is a letter that Kensuke’s son, Michaya, sends to Michael, telling, as Paul Harvey used to say, “the rest of the story.” The novel concludes with Michael noting that a “month after receiving this letter I went to Japan, and I met Michaya. He laughs just like his father did” (163).

Read this book and pay attention to this postscript. As an adult reading this book, you may find it to be terribly maudlin, and I won’t argue with you. But take off your adult eyeglasses, quit looking at this book through the lenses of an English teacher, and discover what this postscript does: it provides a necessary closure to Michael’s and Kensuke’s story. Of course it evokes an emotional response; that’s the purpose of literature. And if it seems a bit crude (and as an adult reading this book, it does) it won’t for younger readers, who have a different set of expectations for what literature has to offer. Read, enjoy, read it again, and enjoy it even more.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2009/12/20/kensukes-kingdom-michael-morpurgo/

good book

I just finished reading Kensuke’s Kingdom (as an adult reader). I enjoyed it, but not as much as Private Peaceful, which is my favourite Morpurgo (so far, I’ve only read a few of his books- his output is so vast). I think you’ve done a great blog post. I particularly like your comparison of the covers.

what was the description of Kensuke’s cave in chapter 7?

It was a good one:

And a bit later on:

The exact opposite of my house.

I am searching for a map of the journey from England to the island or an approximate setting of the island. Any chance anyone knows if one exists and were I might find one? I do see from other postings that a map of the island or Kensuke’s Kingdom on the inside cover of hardcover book. susan

I have only seen this book in softcover, and so was never aware that there was a map. However, I found a PowerPoint presentation made by the Year 6 students at the Dormer Wells school in London (http://www.dormerswells-jun.ealing.sch.uk/Year%206%20work.html) which contained a scan of the map. I cleaned it up a little bit, and you can find the results here: http://images.kjodle.net/kensuki.jpg. Enjoy.

I want to look a kensukes kingdom map of island.

iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii LOVE THIS BOOK