Sometime in the future, on the Gulf Coast of whatever is left of the United States, Nailer works light crew breaking ships. His small stature helps him clamber deep into the bowls of the ship, going after wiring and other small bits of metal.

Sometime in the future, on the Gulf Coast of whatever is left of the United States, Nailer works light crew breaking ships. His small stature helps him clamber deep into the bowls of the ship, going after wiring and other small bits of metal.

It’s dangerous work, and a hardscrabble life where a single slip-up can result in death. Despite working hard, there are still days when there is nothing to eat. Surrounded by signs of obvious wealth (including modern, glossy sailing ships that appear almost every day far to sea), Nailer lives in utmost poverty, always hoping (along with everyone else) for a “lucky strike” that could turn his life around.

After a violent hurricane passes through, Nailer finds a crashed sailing ship just offshore. Exploring it, he finds it full of treasures, and open to salvage provided the entire crew is dead. When he finds a single survivor, a young girl his own age who promises him a reward if she helps him, he is faced with a choice: believe her dubious claims and help her, or kill her and claim the salvage.

Taut with life-or-death situations at nearly every turn, I found myself eagerly reading to the end. Well-conceived and well-written, this book is anything but predictable. It was a finalist for the 2010 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature and was a nominee for the 2010 Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy. Listed on American Library Association’s Young Adult Library Services Association list of Top Ten Best Fiction for Young Adults 2011 list and won the 2011 Michael L. Printz Award.

Response

Part of the role of science fiction is to show us what could have been, or what could be to come. In the latter category, you have everything from poorly written novels that are cheesy retreads of classic SF novels to much of what is passing today as YA literature which is actually science fiction, such as Feed, The Hunger Games, and Ship Breaker. I find it a little curious that most dystopian science fiction is marketed toward the YA market, but it is not marketed as science fiction. In other words, the sort of stuff I would have read in high school and been denounced as a geek for reading it is now mainstream, because it lacks the SF label.

Which is all to the good, really, because most dystopian SF that is marketed as science fiction is not really all that good. The YA market, free of that “SF” label, can approach dystopian themes tangentially, because young people want real stories about real people without getting too much into the technology. Good science fiction is more about the people than the technology (or lack thereof), whereas bad or mediocre science fiction is much more about the technology that it is about the stories. So although Bacigalupi is known as a science fiction writer for adults, this book is not marketed as science fiction for young people.

That said, given the current situation regarding climate change and rising sea levels, it would easy for a book like this to become overly preachy about such things. I don’t have a problem with such themes in a book, but when theme is foregrounded over story, then the book is merely a polemic, and I prefer my books without billboards stuck in the middle. Story must always come first.

The closest it gets to becoming an environmental polemic is tucked away neatly in the middle of the book:

The train curved toward the hulking towers. The shambled outline of an ancient stadium showed beyond the spires of Orleans II, marking the beginning of the old city, the city proper for the drowned lands.

“Stupid,” Nailer muttered. Tool leaned close to hear his voice over the wind, and Nailer shouted in his ear, “They were damn stupid.”

Tool shrugged. “No one expected Category Six hurricanes. They didn’t have city killers then. The climate changed. The weather shifted. They did not anticipate well.”

Nailer wondered at that idea. That no one could have understood that they would be the target of monthly hurricanes pinballing up the Mississippi Alley, gunning for anything that didn’t have the sense to batten down, float, or go underground.(203-4)

That’s not too much, really. “They did not anticipate well.” Heck, we all know that we don’t anticipate well, which is why we’re in just about every mess we’re in. Hindsight is always 20/20. However, like some of the best (and worst) science fiction, this is a sternly moralistic work about the way we treat our planet and how we treat each other. It is an ugly world that Bacigalupi shows us, but because he puts his story first, it is a world impossible not to believe in.

That world has a lot to say about the world we live in right now. Like Atherton, this is a book that can be easily examined from a Marxist literary perspective. If I were putting together a course on Marxist theory for adolescents, this book would easily make that reading list.

Work Cited

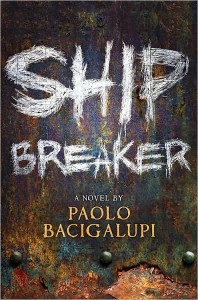

Bacigalupi, Paolo. Ship Breaker. New York: Little Brown, 2010.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2011/07/05/ship-breaker-paolo-bacigalupi/