Blue Baker is just like any other kid who recently lost his father. Except that Blue is writing a story about a savage who lives in Burgess Woods, a savage who doesn’t speak but only communicates through grunts and growls. Blue’s savage terrorizes people like Hopper, who lives to terrorize people like Blue. Despite what people like his mum or Mrs. Molloy, the school counselor, say, it’s isn’t really possible to stay out of Hopper’s way.

Blue Baker is just like any other kid who recently lost his father. Except that Blue is writing a story about a savage who lives in Burgess Woods, a savage who doesn’t speak but only communicates through grunts and growls. Blue’s savage terrorizes people like Hopper, who lives to terrorize people like Blue. Despite what people like his mum or Mrs. Molloy, the school counselor, say, it’s isn’t really possible to stay out of Hopper’s way.

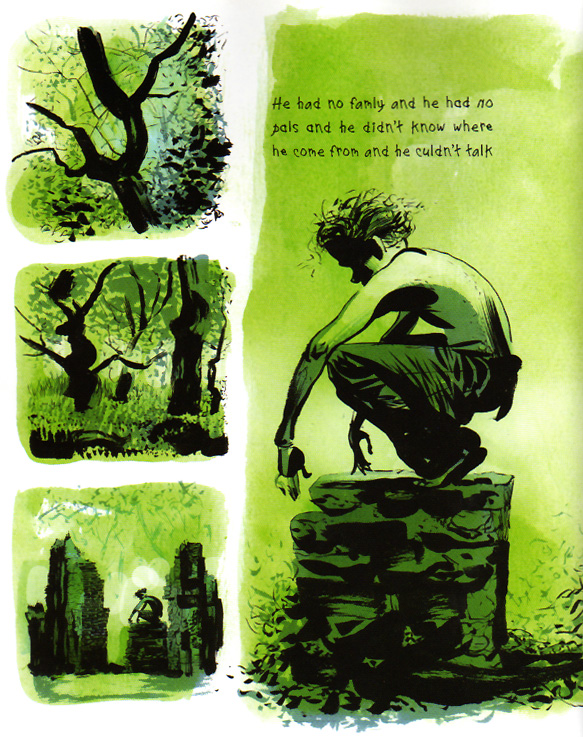

It also isn’t possible to stay out of your story’s way, either. When events in real life begin to resemble those in his story, Blue has to question the line between his imagination and real life:

In English…we had to write stories, so I just got on with the savage’s tale. I scribbled fast and free, and the pages became like the story in my notebooks—scribbles and scrawl and doodles and drawings. And it maybe looked like a mess, but it was a mess that made sense, that made a story on the page, and in my mind that was as vivid and real as the real world. Then I was aware of the teacher, Miss Brewer, standing at my side, looking down at me and my work, and I realized that I was grunting and growling as I wrote. (67)

That’s a passage that will send shivers of recognition down the back of any good writer—the moment you realize that you are no longer in charge and that the story is using you to write itself.

David Almond has crafted a vivid, realistic story of love, loss, and recovery. Anyone seeking to understand that will enjoy the harmony between Dave McKean’s quirky, energetic drawings (the original reason I picked up the book) and David Arnold’s quirky, energetic story.

You can visit David Almond’s website here, Dave McKean’s website here, and read a good interview with David Almond here.

The Missing Father in Kid and YA Lit

Warning: The rest of this post contains spoilers!

The concept of the absent father is not a new one, being old when Odysseus left Telemachus suckling at the breast of Penelope. This motif stretches back hundreds, if not thousands, of years, which makes books such as Roald Dahl’s Danny, the Champion of the World, in which a father is there and yet not there, not there and yet there, such a delight. There are many other books which address the absent father either directly or tangentially. As a teenager, I read Richard Peck’s Father Figure, in which a father is there, but not there, not there, but somehow conspicuously present by his absence. I would later read The Lord of the Rings, in which Frodo first loses the father figure of Bilbo and then Gandalf (and if you’re looking for a topic for an essay—or a dissertation—you could do worse than to consider the role of father figures in The Lord of the Rings and other great works of fantasy). As an adult, I would later read the Harry Potter books, which at times are very concerned with absent fathers and father figures—it seems that everyone who serves as a father figure to Harry is eventually lost, including Severus Snape and Remus Lupin, with the lone exception of Mr. Weasley.

Wow, that’s a lot to get out of an 80-page book that contains a lot of pictures. But what I found extremely interesting is the savage’s muteness, which seems to serve as a metaphor for Blue’s own inability to talk about his feelings.

There was a counselor at school called Mrs. Molloy, who kept taking me out of lessons and telling me to write my thoughts and feelings down. She said she wanted me to explore my grief and “start to move forward.” I did try for a while, but it just seemed stupid, and it even made me feel worse, so one day I ripped up all that stuff about myself, got an old notebook, and started scribbling… (7)

That’s the first page of the book, and on the very next page we meet the savage himself:

The Savage’s muteness therefore, serves as a metaphor for Blue’s inability to express how he feels from the very beginning. Some may consider this odd, but I don’t. Blue cannot really express how he feels, so he creates an alter ego—the Savage—who cannot express himself verbally at all, and because of this inability, he is able to mirror what Blue has been experiencing on a subconscious level. The savage never progresses beyond “agh” and “ugh,” yet he is still able to express himself visually, when he shows Blue the drawings he has made on the wall of his cave.

The Savage’s muteness therefore, serves as a metaphor for Blue’s inability to express how he feels from the very beginning. Some may consider this odd, but I don’t. Blue cannot really express how he feels, so he creates an alter ego—the Savage—who cannot express himself verbally at all, and because of this inability, he is able to mirror what Blue has been experiencing on a subconscious level. The savage never progresses beyond “agh” and “ugh,” yet he is still able to express himself visually, when he shows Blue the drawings he has made on the wall of his cave.

It was me, there on the cave wall. I was drawn in charcoal and colored with the dye form leaves and earth and berries. There I was, sitting, leaning over a desk, writing.…There was Jess, dancing beneath the sun. There was Hopper; with his skull tattoo and his cigarette.…I grunted, muttered. I had no words. The pictures on the cave wall were works of wonder. (74-75)

Here we sense what had been two separate elements, Blue and the savage, becoming one. “How could that be?” Blue asks, noting that he whispers this question “to the savage, to myself” (75), an ambiguous reference.

In some ways, this book reminded me strongly of Evan Kuhl’s The Last Invisible Boy, in which a boy copes with the loss of his father by gradually fading away. But I’ll have more to say about that later, because I can now think of a few books in which things like muteness or invisibility offer kids mechanisms for coping with loss.

Almond, David. The Savage. Illus. Dave McKean. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Candlewick, 2008.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2011/03/31/savage-david-almond/