It took me forever to write about this book, and it’s only now that I realize it’s because I wanted to say a lot more nice things about than I actually can. Which is sad in a way, because looking back, I wish that this book had been around when I was in fifth or sixth grade and looking for something a bit out of the ordinary.

Kid lit is apparently going through a minor art phase; Chasing Vermeer by Blue Baliett and Masterpiece by Elise Broach are two other entries in this field. This is encouraging because—let’s face it—arts education in this country is sorely lacking. And yet, as this book shows, part of the problem is that we can’t let kids just sit back and enjoy the arts: there has to be a lesson, a moral, something that proves that the point of art isn’t just the art itself, but that it has something to teach us. In other words, there has to be a point to the whole thing.

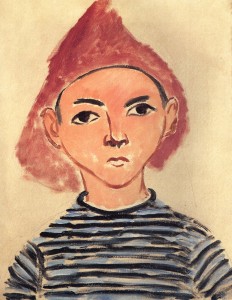

A brief plot summary is in order. Eleven year old Matisse Jones has two problems. The first is that his family is just plain weird, and for your average sixth-grader (which Matisse desperately wants to be), this is not just a minor problem, it’s a major problem. The second is that Matisse is pretty good at painting copies of the paintings in the art gallery in which his mother works, which is not normally a problem—this is why all the adults around him like him. But when the security system is down and he switches his version of Henri Matisse’s Portrait of Pierre with the real one (just to see what it would be like to see one of his own paintings hanging in a museum) and the security system comes back on before he can switch them back, it suddenly becomes a huge problem.

It’s not giving too much away to say that the original painting eventually makes its way back to where it belongs, because the whole problem of which painting is which isn’t really the main conflict in the book. The main conflict is how, or even if, Matisse comes to terms with his highly unusual family. And as to that, gentle readers, I will gladly leave you hanging.

Though an enjoyable read, I found this to be a highly didactic book in many ways, which is part of the appeal to publishers, librarians, teachers, and parents. But to be fair, it is not so highly didactic that it will turn off young readers. In fact, there are moments of high tension that left even me wondering what was going to happen next. (And a big reason that I don’t watch network television is that it is too formulaic—generally I can guess the next joke or plot twist, and therefore, what is the point?) And there are some writing issues which I found distracting.

Despite its faults, there are two reasons that I liked this book.

First, it’s unpredictable. I read a lot of books aimed at this age level, and let’s face it, a lot of them seem as if they’ve come out of a “find and replace” workshop: same ideas, different names. But each time I found myself saying, “Oh yes, I know what’s going to happen next,” I found that I was wrong. Delightfully wrong, in fact. Matisse and his friends and family simply don’t act in the stereotypical way I’ve come to expect children’s lit characters to behave. This is a good thing, although Bragg will sometimes swing for the fences and miss. These mostly deal with issues of masculinity, about which I’ll treat later.

Second, it’s written by an artist. I’m both too old and too jaded to think that anyone writing a book for children doesn’t have some didactic purpose tucked away in the back of their mind. Because the back flap describes Georgia Bragg and her entire family as artists, I was especially interested in what she had to say about art. And I wasn’t disappointed. Early on, when Matisse is painting his copy of Portrait of Pierre, he finds that

“[t]he picture practically painted itself. Everything looked good: the colors, the thickness of the paint, the direction of the brushstrokes and the look on Pierre’s face” (33)

I’m not an artist, but as a writer, I’ve had paragraphs that practically threw themselves together in the same manner. This is an okay passage if you grew up in a family of engineers, but what caught my eye was the mention of “the thickness of the paint.” This is something only an artist would bother to note or point out. Anyone could notice the color in a painting or the expression on the subject’s face, but it takes an artist, or at least someone with more than a passing familiarity with art, to notice how thick the paint is, or the direction of the brushstrokes—two things which are rarely observable in books or prints. It’s possible to throw this line away and the book won’t lose much, but a phrase like this is, for me, what separates this book from so much of the didactic dreck that is all too often thrown at our children, from a seriously well-meant, if as yet underdeveloped talent.

As a further example, Matisse later explains to his brother Man Ray the difference between the genuine Matisse painting and his own copy: “Mine was painted from the elbow down. The real one came from someplace deep inside Henri Matisse” (108).

Until I read this book, I’d never encountered the phrase “from the elbow down,” which strikes me as an expression that is often tossed about by artists, and, more importantly is a very clear metaphor for the difference between a painting which is “art” and a painting which hangs in the lobby of a cheap motel. (Although, according to postmodern theory, that black velvet painting of dogs playing poker isn’t necessarily to be valued any differently from a painting by, say, Henri Matisse, which leaves me conflicted to no end. I mean a Matisse is a Matisse, but dogs? And they’re playing cards! Does it get any better?)

All in all, I liked this book, despite its somewhat didactic nature, but I wanted to like it a great deal more than I did. And here is my main issue with this book.

I don’t like books with a gimmick. And the biggest gimmick here is that the main character is eleven-year-old Matisse (as in Henri Matisse), who has both an older sister named Frida (as in Frida Kahlo, the Mexican artist) and a younger brother named Man Ray (after the American artist). Now, throwing in the names of such famous artists is probably meant to appeal to “grown-ups who know what’s good for kids” in the same way that all those nutrition labels on sugary cereals are meant to appeal to the adults who buy the cereals rather than the kids who actually eat them. (Seriously, parents, do you ever bother to read the nutrition information on these things?) The thing is, I could probably forgive someone naming their child Matisse or Frida. After all, drunken, romantic weekends in Paris do happen. But nobody names their child “Man Ray.” Even Man Ray’s parents didn’t name him Man Ray. They named him Emmanuel Radnitzky.

Besides that, there were, on occasion, clumsy metaphors. For example, after Frida dyes her hair purple, Matisse observes that “Mom and Dad acted like they didn’t even care that Frida’s hair was the color of a skittle” (16). I don’t eat Skittles, but don’t they come in a variety of colors, of which precisely one is purple? The purpose of a metaphor is to make things clear, or at least less muddy; such an imprecise metaphor doesn’t do much to help the reader (especially if said reader is young and unfamiliar with Skittles). Later, Matisse notices that his father’s new recipe “tasted like chicken but with a funny flavor, as if the pig had spoken Spanish or something” (17), which strikes me as not only unclear, but vaguely racist as well, which, no doubt, was not the author’s intention.

Then, too, there are some amazing lapses of verisimilitude. At one point, Matisse gets out of the back of a police car on his own, something which is not possible in any jurisdiction (122-3). It’s a little slip, however, one which bothered me more as an adult who knows better, and likely wouldn’t bother juvenile readers.

There are two other such lapses I want to point out, and here I’ll finally get to those issues of masculinity I mentioned earlier. In the first, Matisse and his mom drop off Toby at his house, and, as Matisse says, “[w]ithout thinking we gave each other a hug” (65). Later, Toby tells Matisse, “[y]ou’re my best buddy, Matisse,” to which Matisse replies “[y]ou’re my best buddy too” (131). I don’t doubt that eleven-year-old boys feel this way; it’s just that I’ve never seen them express such feelings. But, never mind; this is the postmodern age–you can choose whichever masculinity you wish. But I would point out that both of these scenes were written by a female author, and thus someone who has never been an eleven-year-old boy (or his best buddy), which makes these two scenes a weakness, but I would also point out that both scenes take place at points of high emotional conflict, in which case such out-of-character behavior tells us a lot about the characters in question, which makes such scenes a strength, but as a guy, I still found them a little less than believable. Like I said, Bragg likes to swing for the fences, and if she misses against such a strong pitch, it’s not just forgivable, but rather, admirable for being there in the batter’s box to begin with. But this being a postmodern era and all, I’ll leave it up to you to decide whether it’s a hit or a whiff.

In fact, while we’re talking about the new masculinity (which can be every bit as restrictive as the old masculinity—meet the new boss, same as the old boss), Bragg’s portrayal of Matisse Jones is rather interesting in that he isn’t the stereotypical “artistic” kid. He’s not an outsider (although he’s hardly a complete insider, either), he’s not nerdy, he’s not gay, and best of all, he’s not the Tortured Soul with a Poetic Heart. He’s just a kid whose more interested in, and better at, making art than making a touchdown.

One of the main themes is the question of what does or doesn’t constitute art, which is going to get us into all sorts of problems, from the point of postmodernism. Matisse gets this question answered for him by none other than Pierre Matisse (son of Henri and subject of the painting in question), in a scene which seems a little too didactic for my own tastes, but which I doubt will hardly bother the average middle school reader.

No, what I find more disturbing—or amusing, depending on my mood—is the subtext that is strongly at work throughout the entire book. A common unsophisticated response to Modern Art (with a capital “M” and a capital “A”)—so common it’s almost a cliché—is “You call that art? My kid could have painted that.” Well, in this case, a kid did paint that, and the adults around him (who work in an art museum, and are therefore, one presumes, very sophisticated when it comes to modern art) can’t tell the difference. Admittedly, eleven-year-old Matisse is very good at copying the works of Henri Matisse and other artists, but that’s precisely the point—if a painting can be duplicated by a talented but otherwise unexceptional child, is it really art? And if it is, is the copy art as well? Pierre Matisse would argue “no,” since the copy is only painted “from the elbow down,” but a really good art forger would argue just the opposite. (See the Lovejoy series by Jonathan Gash, for instance.)

So the question is, what if Matisse Jones had really put his heart and soul into copying a painting, and not just painted it from the elbow down (there’s that expression again–sorry, but I just love it too much not to use it), would that painting be art? Could young Matisse even be capable of executing such a painting?

Which leads us back to the question of what constitutes art. If I put my heart and soul into this entry, if it’s written from heart and not just from the elbow down, is it art? Or, because of its ephemeral electronic nature, is it merely so much cyber-babble no matter how much of myself I put into it? Thus, even though Matisse gets his definition of what is art (or at least, Pierre’s definition of what is art, which is probably Georgia Bragg’s definition of art), the overall question still remains: what is art?

And if this seems like a lot of theory to burden the spine of a book aimed at middle-schoolers, keep in mind three things. First, from her photograph on the back flap, Ms. Bragg appears to be a lot less than sixty-five years old, and thus, pretty firmly in the post-modern era. Second, this is subtext we’re talking about. It’s there if you want it or see it, but if you don’t, it doesn’t mean that you won’t or can’t enjoy this book. (This is a book aimed at middle-schoolers, and the last time I checked, most middle-schoolers didn’t even know that there was such a word as “subtext,” much less what it meant or implied. So relax. Take a deep breath and just relax.) Third, this is me we’re talking about, and I think about postmodernism and subtext a lot, which means that for the average person, I overthink these things. You could read this book and come away with a completely different idea of its subtext—in fact, I bet you do, because you have a different background than I do. And if you do, I want to hear about it. Drop a comment.

Chapter book, middle school and up. Recommendation: not destined to be a classic, but worth a quick read. Most kids will like it.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2010/04/02/matisse-on-the-loose-by-georgia-bragg/