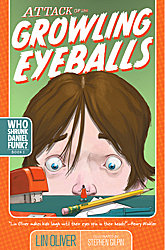

I’ve reviewed the Hank Zipzer books twice, and while I’ve had plenty to say about Hank Zipzer and Henry Winkler, I said nothing about Mr. Winkler’s cowriter, Lin Oliver, because I had never heard of her until I encountered the Hank Zipzer books, and knew nothing of her writing. So I did what I always do in these situations: I headed to my local library to see what I could find. And what I found was book 1 in the “Who Shrunk Daniel Funk?” series, Attack of the Growling Eyeballs.

I’ve reviewed the Hank Zipzer books twice, and while I’ve had plenty to say about Hank Zipzer and Henry Winkler, I said nothing about Mr. Winkler’s cowriter, Lin Oliver, because I had never heard of her until I encountered the Hank Zipzer books, and knew nothing of her writing. So I did what I always do in these situations: I headed to my local library to see what I could find. And what I found was book 1 in the “Who Shrunk Daniel Funk?” series, Attack of the Growling Eyeballs.

I did not have high expectations for this book because of her association with the Hank Zipzer books, which I admit is unfair to both the book and to Lin Oliver, and that bothers me. It doesn’t bother most kids, however; if you’ve written one book they don’t like, they’re not likely to pick up another one. I wasn’t disappointed, either. Right off the bat, Oliver breaks the fourth wall in the prologue by having Daniel address the reader:

Let’s be honest. I have no idea what a prologue is.

And I bet you’re not too clear on the concept either.

The only think I know is that a prologue comes at the beginning of a book. If you ask me, and I know you didn’t, I think books should start with a map…

I really don’t like it when characters on TV shows break the fourth wall and directly address the audience, because it usually doesn’t work. (Malcolm in the Middle is a rare of example of one that did.) In literature, it happens a bit more often, but it’s still difficult to get the tone just right. J.D. Salinger mastered it in The Catcher in the Rye, and a few have come close to his success (Russell Banks in Rule of the Bone comes to mind), but it’s too easy to err on the side of goofy, as in this case. If this book were written as a journal or a diary, I could see it, but, hey, if you’re a kid and you have no idea what a prologue is, then why would you write one?

All is forgiven, however, because of one little word: map. It has long been my contention that boys like books with maps in them, and most guys like books with maps in them. (The only kind of map we don’t like is a road map.) The Chronicles of Narnia, The Lord of the Rings — even Winnie-the-Pooh — all begin with maps. (One clue I had that J.K. Rowling might not be male was that there were no maps in the first Harry Potter book. I think that if a man had written it, he would have been more likely to include one.)

And the next page is indeed a map of Daniel Funk’s room, complete with a “La-Z-Boy (ultimate chair),” “Underpants Valley,” and “Stinky Sock Mountain,” a brief snapshot of Daniels’ room in which microcosm and macrocosm will lose all meaning.

A brief synopsis is in order. Eleven-year-old Daniel Funk, raised in a family composed completely of females (including the dog, cat, hamster, lizard, and Siamese fighting fish), finds himself mysteriously shrunk down to the “about the size of the fourth toe on [his] left foot” (12). A few moments later, just as mysteriously, he finds himself full-sized again. What is at the cause of all this shrinking and un-shrinking is something that only his father’s grandmother, Great Granny Nanny, has a clue about it.

Needless to say, Granny Nanny has a lot more than a clue. And for a boy who has grown up without any male relatives around (“I don’t remember [my dad] too well,” Daniel tells us, “except that he always wore big hats and could whistle like every kind of bird” [25]) she is also the link to what he has always wanted: male companionship in the form of a miniature twin brother, Pablo Picasso Diego Funk. (Is it significant that Granny Nanny is his dad’s grandmother, rather than his mother’s? I’ll let you decide, but I’ll give you a hint about what I think: subtext.)

So Daniel learns about Pablo, and they have some adventures together which are funny and hair-raising at the same time. I found myself eagerly turning the pages, wanting to find out what happens next, and really, really (and I mean really) enjoying this book.

There are some issues with this book, mainly in the image of Daniel “trying to show off the one hair that I’ve sprouted on my man-chest” (33). I saw the same thing in the movie Milk Money years ago, and believe me, eleven-year-old boys (or boys of any age, for that matter) just aren’t concerned about chest hair. This issue arises mainly because Lin Oliver has never been an eleven-year-old boy (which you can hardly fault her for) and so could hardly be expected to write authentically about a boy’s views on puberty. And while she doesn’t get the voice right 100% of the time, it’s much more believable than in the Hank Zipzer books.

The far more important issue — that of who Daniel identifies with and why — is something that Oliver does do well. She explores the topic adequately, meaning that within the confines of a children’s book, it’s there if kids want to notice it and talk about it, and if they don’t, well, there’s a thrilling car chase and a gigantic hissing cockroach to corral, which is more than fun enough to make up for the bit of treacle at the end. (Is it just me, or is it now okay for boys to show their affection for one another? I had this same issue with Matisse on the Loose, as well, another book about boys written by a woman.)

I haven’t classified this book as a “book for guys” for a couple of reasons. First, I really don’t think Lin Oliver meant it to be just for boys, although most boys could relate well to a lot of the issues in this book. And second, she’s not a guy. (As Christopher John Francis Boone might say: “This makes her an outsider.”) I really think that most of the successful literature aimed directly or tangentially at boys is written by people who used to be boys themselves, such as Jack Gantos or Jon Scieszka. Not that there aren’t exceptions. There are always exceptions — Jean Craighead George’s My Side of the Mountain comes to mind here. But more about that later.

Most importantly, this is a fun book. Kids will be entertained by it, from the title — which gives off a vague 1950’s drive-in horror flick — to the quirky, expressionistic illustrations by Stephen Gilpin. I initially sighed when I saw that it was the first in a series (the success of Harry Potter has pretty much ensured that every new kidlit book will have a number on the spine), but if Lin Oliver can keep up the vitality and originality, it will be a series most kids will enjoy.

Ages: 8-12. Recommendation: A good, fun read, with more to come.

Oliver, Lin. Attack of the Growling Eyeballs. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008. (Illustrated by Stephen Gilpin.

https://bookblog.kjodle.net/2010/08/08/attack-of-the-growling-eyeballs-lin-oliver/